The Principles of Adapting Yoga to Individual Needs | Mark Whitwell

TKV Desikachar on T. Krishnamacharya

In 1995, when Desikachar’s book The Heart of Yoga was published, we did a series of interviews in New Zealand in which Desikachar spoke at length about his father’s life and approach to teaching.

Desikachar described his father, Tirumalai Krishnamacharya (1888–1989), as an extraordinary person who lived for one hundred useful years; as a man whose thirst for yoga knowledge eventually took him to the high plateaus of the Himalayas where he lived with his teacher Ramamohan Brahmacari for seven and a half years; and as a man who gave his life to translating an ancient body of wisdom into the modern world for all people.

Above all, Desikachar emphasised his father’s insistence that Yoga must be carefully adapted to the individual, not the individual to the Yoga. But this idea, he clarified, was by no means his father’s invention.

“Our ancestors have always emphasised that everything must be adapted to the given situation. It is not only yoga, even rituals and worship must be adapted.

I remember a long time ago in 1937 when an American lady named Indra Devi came to study with my father. He taught her in a way that was different from the way he taught the young Indians based upon how her body was.

‘Go slow by slow. Step by Step,’ he said to her. ‘Do not force the body. And always breathe very slowly.’

“With younger people he was teaching very differently because he knew that it had to be adapted. So it is not a new concept that we need to adapt. It is in the tradition and we just carry on!

The way it was adapted in the previous century may be different from the way it was adapted in the next century because of the current conditions. But we have the tools to do that. This is one of the requirements of a teacher. He should know how to adapt.”

How to Adapt a Practice

When considering how to adapt a practice there are some useful principles to consider. Firstly, the practice given must be appropriate to the student’s body, their physical strength, and the quality of their breath.

Secondly, the student’s age and what stage of life they are in must be considered: is the student in their elderly years and thus requiring a more reflective, meditative practice? Or are they young and strong and requiring a great deal of invigorating asana? Thirdly, any health issues can be discussed and appropriate practice to support the student’s return to full health.

Finally, the student’s cultural background is crucial to consider. Krishnamacharya was very clear, for example, that no Hindu chants were to be given to Muslim or Christian students; rather, a mantra or chant from the student’s own culture should always be used. Religious language should not be used for non-religious students, and vice versa.

Adapting Yoga therefore is quite a sensitive matter. There needs to be a real relationship of trust there and the teacher must really know the student well. If that trust and mutual affection is there (sraddha) it is golden.

The Problem of Modern Yoga

As we reflect today on the short history of modern yoga in the west, we can trace much of what went wrong to the abandonment of the ancient principle of adapting to the individual.

Yoga has been turned into a commercial enterprise in which one-size-fits-all sequences are sold to a gullible public; where asana is taught as a muscular struggle without respect to the breath; and where teachers pass on spiritual psychologies of spiritual and psychological struggle toward an idea of ‘becoming’ an ideal human being. In other words, the uniqueness of the individual is denied and they are put through cultural patterning.

We have travelled a long way from the humble, sincere and intelligent origins of Yoga. In the ancient culture of Veda, the very heart of Yoga itself was the relationship between the teacher and the student: a relationship of mutual affection and respect. The teacher respects the student no matter who they are or whatever difficulties they may have in the aberrations of the world.

Krishnamacharya would go so far to say that the teacher cares more for their student than for themselves. This approach of deep care comes from the understanding in Veda that the teacher and the student are not separate little selves (ego “I’s”). But rather, that there is only the One Reality (or God) arising as every one and every thing.

It is unimaginable in today’s world and a tall order indeed in the Western mind of survival and every man for himself; but the recognition of Oneness that went beyond any individual point-of-view was the starting point of Yogic culture. It was a recognition that was and is tacitly felt at the heart.

No More than a Friend and No Less

Krishnamacharya rejected the available celebrity of spiritual and religious India: the cultural hierarchy where a charming person on a special chair and with a special social position tells everyone how to live.

He walked out of what his friend U.G. Krishnamurti called “the social dynamic of disempowerment” and simply lived a life of Yoga. From his home in Madras he set about teaching actual practice to ordinary people. He would always teach in one-on-one private meetings. He had an agenda to care for people and was not a Yoga businessman.

“It was not good for my bank manager,” he would quip.

Thanks to the pioneering work of Krishnamacharya and his son Desikachar, real Yoga is available to any person today as a profound tool to empower our lives. Although actual teachers informed of the principles he brought forth are rare, they do exist; like points of light scattered across the globe.

Often, the teacher arrives in a student’s life at the right time by grace and good luck. Otherwise, it is recommended that you do everything you can to seek a good teacher out and receive a real Yoga education.

*The heart of Yoga online studio is now live with weekly classes and gatherings. If you have been moved by anything you have read you would be most welcome to join us. The studio is by-donation and designed to support any person to begin a home Yoga practice that is perfect for them.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

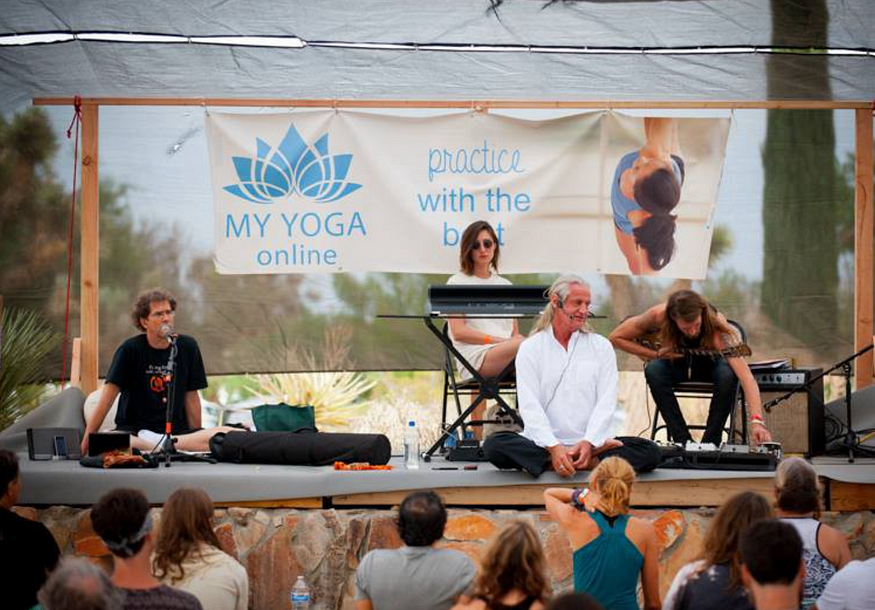

Mark Whitwell has been teaching yoga around the world for many decades, after first meeting his teachers Tirumali Krishnamacharya and his son TKV Desikachar in Chennai in 1973. Mark Whitwell is one of the few yoga teachers who has refused to commercialise the practice, never turning away anyone who cannot afford a training. The editor of and contributor to Desikachar’s classic book “The Heart of Yoga,” Mark Whitwell is the founder of the Heart of Yoga Foundation, which has sponsored yoga education for thousands of people who would otherwise not be able to access it. A hippy at heart, Mark Whitwell successfully uses a Robin Hood “pay what you can” model for his online teachings, and is interested in making sure each individual is able to get their own personal practice of yoga as intimacy with life, in the way that is right for them, making the teacher redundant. Mark Whitwell has been an outspoken voice against the commercialisation of yoga in the west, and the loss of the richness of the Indian tradition, yet gentle and humorously encouraging western practitioners to look into the full depth and spectrum of yoga, before medicalising it and trying to improve on a practice that has not yet been grasped. And yet Mark Whitwell is also a critic of right-wing Indian movements that would seek to claim yoga as a purely hindu nationalist practice and the intolerant mythistories produced by such movements. After encircling the globe for decades, teaching in scores of countries, Mark Whitwell lives in remote rural Fiji with his partner, where Mark Whitwell can be found playing the sitar, eating papaya, and chatting with the global heart of yoga sangha online. Anyone is welcome to come and learn the basic principles of yoga with Mark Whitwell.

Comments

Post a Comment